Australia’s child support system was designed to be boring.

It was meant to be predictable, largely automated, and resistant to discretion. Parliament deliberately embedded a formula so that outcomes would not depend on personalities, persuasion, or power. The system’s legitimacy rested on one idea: decisions would be made by rules, not people.

That is why the quiet outsourcing of core child support decision-making — at a cost approaching $12 million for just the two individuals in question since 2019 — should concern far more people than just those directly affected by the scheme.

The issue is not simply who was paid. It is what that payment says about how government now governs.

When a rules-based system no longer trusts itself

Child support assessments are often described by the agency itself as formula-driven. Inputs go in, an amount comes out. Discretion exists, but it is narrow and reviewable.

In such a system, internal capability should be sufficient. If a function can be reduced to guidance notes, decision trees, and training modules, it should not require premium-priced external labour.

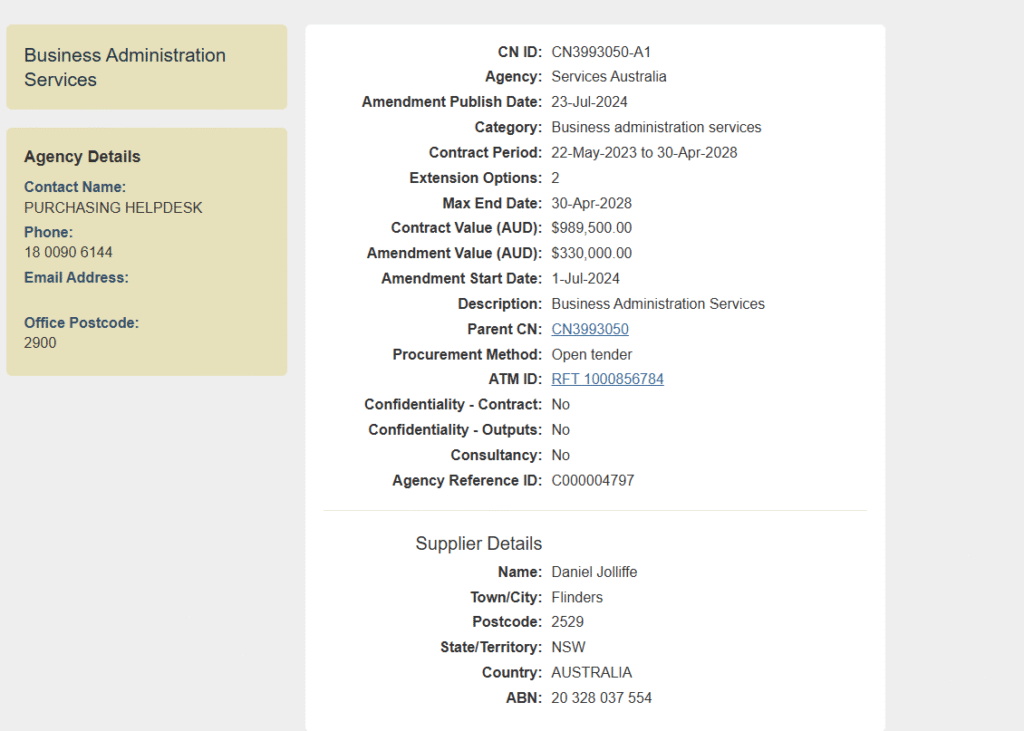

Yet since 2019, two private contractors — Daniel Jolliffe and Sarah Jolliffe — have been paid close to $12 million to perform child support decision-making functions on behalf of Services Australia.

That single fact raises a more profound question than any allegation of individual wrongdoing:

Why does a rules-based system now require outsourced decision-makers at all?

Outsourcing as a substitute for institutional confidence

In public administration, outsourcing is often justified as a way to buy specialist expertise, surge capacity, or independent review. None of those explanations sit comfortably here.

The work being outsourced is not novel.

It is not episodic.

It is not policy design.

It is the ongoing application of existing law.

When a government outsources routine decision-making, it is not buying expertise. It is compensating for something else — typically staff churn, loss of institutional memory, or internal risk aversion.

In other words, outsourcing becomes a way to transfer responsibility.

If a decision later proves controversial, the organisation can point outward rather than inward.

The Jolliffes as a case study, not the core problem

Daniel and Sarah Jolliffe should be understood less as the story itself and more as an illustration of how far this practice has gone.

They are related.

They have operated in the same functional space.

They have received extraordinarily large sums for work that is, by design, administrative.

None of that, on its own, proves impropriety. But it does expose how concentrated outsourced authority has become — and how lightly the public seems to have been consulted about it.

In most areas of government, paying related contractors millions of dollars to exercise delegated statutory power would attract intense scrutiny. In child support, it has occurred largely out of sight.

That invisibility is itself part of the problem.

When accountability becomes blurred

One of the most underappreciated risks of outsourcing decision-making is not cost — it is accountability.

When a public servant makes a decision, there is a clear chain of responsibility: delegation instruments, codes of conduct, internal review, and ultimately ministerial accountability.

When a contractor makes that same decision, the chain fragments.

Parents affected by child support decisions already struggle to understand who made a decision, on what basis, and how to meaningfully challenge it. Outsourcing does not simplify that process. It complicates it.

Even something as basic as consistent identification of decision-makers becomes murky. Internal documents reviewed by theguv.com.au show the same individual referred to under different name variations across correspondence. That may be clerical. But in administrative law, precision matters.

Power exercised without clarity erodes trust.

The cost question misses the deeper issue

Public debate often gets stuck on the headline number: $12 million.

That number matters. Taxpayers are entitled to ask whether it represents value for money.

But the more serious question is what that money is really buying.

If it is buying the application of a formula, then the system has failed at its most basic level.

If it is buying discretion, then Parliament’s intent has been quietly overridden.

If it is buying risk insulation for the agency, then accountability has been displaced rather than addressed.

None of those outcomes is benign.

Children are not helped by institutional drift

The child support scheme exists for one reason: to provide children with stable, reliable financial support.

That goal is undermined when systems become opaque, decision-making becomes distant, and enforcement becomes the primary tool for compliance.

Outsourcing does not make decisions more humane. It does not make them more consistent. And it does not make them easier to challenge.

In practice, it often does the opposite.

What this really tells us about modern government

This is not just a child support story. It is a governance story.

It is about how government agencies respond when systems designed to be simple become politically sensitive. It is about how responsibility is shifted when internal capacity erodes. And it is about how administrative power expands quietly, without public debate.

The question is not whether Daniel and Sarah Jolliffe should have been paid.

The question is why the state no longer trusts itself to apply its own rules.

Until that question is confronted openly, controversies like this will continue to surface — not because of individual actors, but because of a system that has lost sight of its original design.

And when that happens, it is not just parents who lose confidence.

It is the public.